Wednesday, February 07, 2007

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

The last ever post here

Dear folks. I have defected to Seed Blogs on a promise of fame, fortune and women. So this will be my last ever post at this site. The new link is here, and the news feed in Atom form is here. It's been fun, so drop by for a chat.

I will repost some oldies from here to begin with, and continue our discussions.

I will repost some oldies from here to begin with, and continue our discussions.

Friday, June 09, 2006

A blogging delay

Dear readers, for reasons that will shortly become clear, there is a blogging delay here. Hmm... "blogging" in that context sounds like a swear word... "another blogging delay! Dammit!"

Stay tuned and in a day or so All Will Be Revealed.

Stay tuned and in a day or so All Will Be Revealed.

Monday, June 05, 2006

Biologically feasible political systems

I often wonder what goes through the minds of those who propose utopian political ideals that turn out to become the worst of all possible dystopias, like Leninism or Maoism, or for that matter the extreme laisse faire capitalist conservatism. For it appears to me that these systems would work just fine, if only they didn't involve any human beings. And that raises an interesting question in my mind, and I hope, yours too. What sorts of political systems are biologically feasible for human beings? As Aristotle said, Man is a Political Animal, but what sort of political animal?

Any political system that relies upon purely rational behaviours, for example, is right out. It is often noted that economic and political behaviours are like the games of game theory - any system that relies on a rational outcome, is vulnerable to the free rider effect, as in Garrett Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons. Here's a case in which a shared common resource (the commons, on which each farmer may graze on sheep) is systematically destroyed. One farmer (the freerider) thinks to get an edge on his competitors and graze two sheep. The other soon find that to keep up, they must do this also. Eventually, the commons is overgrazed, but every participant in its destruction has acted in a rationally self-interested manner.

But worse than this, it may pay not to be rational. Suppose you have a Vulcan society. Each is given according to ability calculated rationally, and each accepts this, in that, as Spock said channelling James Mill and Jeremy Bentham, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. All it takes to subvert that little society, in the absence of draconian sanction, is for one member to act irrationally, and take their own needs as paramount. They will cause others to rationally reflect that if that is happening, there will be a point at which it pays individually to subvert the rational society.

Others, such as Marx, Engels and Lenin have argued that society should be just. A just society does not permit one person to own or control others or their means of production. But it turns out that the ordinary person doesn't see it that way (because of "false consciousness") and so there needs to be an elite (the political proletariat) that judges how things should go on their behalf. Good intentions. It led to the Gulag.

One could multiply examples almost indefinitely. The French Revolution. Jonestown. Finnish utopian colonies, the Philadelphians, the Colonia Dignidad, and a range of American experiments.

Why don't these work? Well, for one thing, it seems that they rely on a particular anthropology - of humans as rational, or spiritual, or open to free love, and so on, all of which are simply implausible as depictions of real humans. But it has for a long time been a Bad Thing to talk about Human Nature, which leads to Essentialism, Racism, Fascism (itself a utopian vision) and ultimately Blindness. But while there are a large number of apologetics for the status quo in the application of ethology to human society, sure enough, most of the time this has relied upon taking distant analogies from, among other things, gazelles, geese, wasps, bees, and caricatures of apes in order to argue that way. Few seem to have tried to argue from the observed and actual human ethological traits to what is a feasible human social structure.

Since I have no internal warning systems of professional suicide, I am going to try to sketch, very roughly, what I think these traits might be, and to discuss how this might affect our quest to form a decent and sustainable society. Feel free to chip in, either with criticisms or suggestions.

Our questions are these:

1. What sort of social animal are human beings? What are the basic social structures of the human animal "in the wild"? We might indeed wonder if there is such a beast as "in the wild" for humans.

2. How do these traits affect us in large societies? Is there something novel in our sedentary and urbanised lifestyles that we did not previously express?

3. Is our social nature constrictive? That is, can we establish a social order that escapes, modifies or completes our biological dispositions?

Others will come to mind.

Any political system that relies upon purely rational behaviours, for example, is right out. It is often noted that economic and political behaviours are like the games of game theory - any system that relies on a rational outcome, is vulnerable to the free rider effect, as in Garrett Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons. Here's a case in which a shared common resource (the commons, on which each farmer may graze on sheep) is systematically destroyed. One farmer (the freerider) thinks to get an edge on his competitors and graze two sheep. The other soon find that to keep up, they must do this also. Eventually, the commons is overgrazed, but every participant in its destruction has acted in a rationally self-interested manner.

But worse than this, it may pay not to be rational. Suppose you have a Vulcan society. Each is given according to ability calculated rationally, and each accepts this, in that, as Spock said channelling James Mill and Jeremy Bentham, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. All it takes to subvert that little society, in the absence of draconian sanction, is for one member to act irrationally, and take their own needs as paramount. They will cause others to rationally reflect that if that is happening, there will be a point at which it pays individually to subvert the rational society.

Others, such as Marx, Engels and Lenin have argued that society should be just. A just society does not permit one person to own or control others or their means of production. But it turns out that the ordinary person doesn't see it that way (because of "false consciousness") and so there needs to be an elite (the political proletariat) that judges how things should go on their behalf. Good intentions. It led to the Gulag.

One could multiply examples almost indefinitely. The French Revolution. Jonestown. Finnish utopian colonies, the Philadelphians, the Colonia Dignidad, and a range of American experiments.

Why don't these work? Well, for one thing, it seems that they rely on a particular anthropology - of humans as rational, or spiritual, or open to free love, and so on, all of which are simply implausible as depictions of real humans. But it has for a long time been a Bad Thing to talk about Human Nature, which leads to Essentialism, Racism, Fascism (itself a utopian vision) and ultimately Blindness. But while there are a large number of apologetics for the status quo in the application of ethology to human society, sure enough, most of the time this has relied upon taking distant analogies from, among other things, gazelles, geese, wasps, bees, and caricatures of apes in order to argue that way. Few seem to have tried to argue from the observed and actual human ethological traits to what is a feasible human social structure.

Since I have no internal warning systems of professional suicide, I am going to try to sketch, very roughly, what I think these traits might be, and to discuss how this might affect our quest to form a decent and sustainable society. Feel free to chip in, either with criticisms or suggestions.

Our questions are these:

1. What sort of social animal are human beings? What are the basic social structures of the human animal "in the wild"? We might indeed wonder if there is such a beast as "in the wild" for humans.

2. How do these traits affect us in large societies? Is there something novel in our sedentary and urbanised lifestyles that we did not previously express?

3. Is our social nature constrictive? That is, can we establish a social order that escapes, modifies or completes our biological dispositions?

Others will come to mind.

Saturday, June 03, 2006

Evolution and irony in the yard

A funny story on a site called Community Press about one woman's struggle against dandelions in the yard makes a nice followup to my piece on lawns a while back. In case the link changes, I will give the story here (and here is the direct link):

Moreover I sometimes suspect that the reason why humans have culture is because they have mothers who insist that there is only one right way to do things (even when you are in your 50s), acting as a cultural brake against change. Think of mothers as a kind of memetic repair mechanism...

Tales from the imperfect rural wife: Chuck had it all wrong in the survival gameThe irony comes from the fact that Chuck did actually consider female choice in evolution, in a rather different context, but more from the fact that dandelions have no sex. They are clonal organisms that reproduce from parts if disturbed. Slash them as much as you like, they will keep coming back. Survival of the most stubborn indeed.

by Paula Cassidy

06.02.06

I had just chopped off their heads, but by the next morning, this lawn full of infiltrators resurrected to full attention, awaiting the next bloody battle, standing there semi-headless, taunting me with their “Darwinian survival of the fittest chant.” Chemical warfare crossed my mind, but my heart leans ever so tenderly to the possibility of a happy, healthy planet and Kyoto Protocol and such—unlike our glorious western leaders who live in some confused environmental denial bubble. The low tech war was on. May the most stubborn species win.

History tells of a carpenter that forever changed our lives. Although golf courses and manicured suburban homeowners may deem him the messiah, this carpenter didn’t wander the lands guiding the spiritual walk of the multitudes. Edwin Beard Budding invented the first lawn mower. His 1830’s patent even touts that country gentlemen would not only be amused by his invention, but would also reap the rewards of a little healthy exercise. Country gentlemen. Right then. To the present, where women rule the powerful motorized riding lawn mower, no longer sitting pretty on the sidelines, sipping lemonade in tight corsets and poofy dresses. Vanity mirror? Forget about it. Who wears lipstick to battle?

I roll my engineless reel mower about thirteen times over the same dandelion stem. The mower was a Mother’s Day gift, but before a mob of sympathetic mothers disperse to lynch my husband, it should be noted that it was a gift I had requested; hindsight brought on by frustration, finds me pining for the sapphire ring or a new toaster. No fuel. No noise. No environmental impact. Great cardio workout. The concept was great on paper, but the reality stood before me, relentlessly clinging to life and limb on acres of grass. I roll over the dandelion one more time, and one more time it bends, side stepping its fate. Stubbornness is something we both had in common. It refused death and I refused the effort to bend over and pull it out. Stalemate.

And without warning, like a trumpet sounding in the high afternoon, I hear the call of the machine—the lure of the green John Deere, parked alone and abandoned in the barn, inside the mechanical perimeters of my husband’s fleet of un-environmentally friendly toys and gadgets. Now the dilemma. Stick to my ecological and heart healthy guns, or cave like a hypocritical jellyfish so I can kill me some dandelions real fast-like, and get on with my day. What’s a girl to do?

“You want to use the riding mower, don’t you? Taking too long, eh?” Ah, thank goodness for sarcastic husbands, because without them, how would we women justify our intrinsic stubbornness. Farewell green champion, may you sit idly in the barn, for destiny calls me to the front yard. My clipping shears in hand, I head into battle, the last samurai, facing each adversary one-on-one, with the mutual respect of a true warrior. Snip. Snip. Snip. Our man Charles Darwin got it all wrong, because he failed to consider the female fight for equality. Fittest? No way. Survival of the “stubborn-est” is the best insurance for species predominance.

Moreover I sometimes suspect that the reason why humans have culture is because they have mothers who insist that there is only one right way to do things (even when you are in your 50s), acting as a cultural brake against change. Think of mothers as a kind of memetic repair mechanism...

Friday, June 02, 2006

The Synthesis and historiography

In an execrable display of taste, Rob Skipper at hpb etc. has linked to this blog, and discussed the Michael Ghiselin quote I put up a few days ago. He rightly notes the standard story is a bit harsh, and suggests some extra reading (to which I would add the series of papers from a special issue of Journal of the History of Biology last year, in particular Jon Hodge's article).

I would like to add, though, that the Synthesists themselves were pretty good at mythmaking when it came to history. In particular, but not restricted to, Ernst Mayr's history of biology. Although this may sound harsh, Mayr has referred to his “precursors” as “prophetic spirits” (Mayr 1996: 269), noting “how tantalizingly close to a biological species concept some of the earlier authors had come” (Mayr 1982: 271), and claimed that “Buffon understood the gist of it” and the early Darwin also (Mayr 1997: 130), thus claiming authoritative precursors. Mayr spends considerable ink defending himself from the charge of reinterpreting history in a whiggist manner in chapter 1 of his 1982 (pp11-13) and yet he is still perhaps the best example of this kind of progressivist triumphalism.

And that is why I quoted Ghiselin.

Smocovitis, Vassiliki Betty (2005), "'It Ain't Over 'til it's Over': Rethinking the Darwinian Revolution", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):33.

Ruse, Michael (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution, as seen in 1979 and as seen Twenty-Five Years Later in 2004", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):3.

Hodge, Jonathan (2005), "Against "Revolution" and "Evolution"", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):101.

Herbert, Sandra (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution Revisited", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):51.

Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution as Viewed by a Philosophical Biologist", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):123.

Mayr, Ernst (1982), The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

——— (1996), "What is a species, and what is not?" Philosophy of Science 2:262–277.

——— (1997), This is biology: the science of the living world. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

I would like to add, though, that the Synthesists themselves were pretty good at mythmaking when it came to history. In particular, but not restricted to, Ernst Mayr's history of biology. Although this may sound harsh, Mayr has referred to his “precursors” as “prophetic spirits” (Mayr 1996: 269), noting “how tantalizingly close to a biological species concept some of the earlier authors had come” (Mayr 1982: 271), and claimed that “Buffon understood the gist of it” and the early Darwin also (Mayr 1997: 130), thus claiming authoritative precursors. Mayr spends considerable ink defending himself from the charge of reinterpreting history in a whiggist manner in chapter 1 of his 1982 (pp11-13) and yet he is still perhaps the best example of this kind of progressivist triumphalism.

And that is why I quoted Ghiselin.

Smocovitis, Vassiliki Betty (2005), "'It Ain't Over 'til it's Over': Rethinking the Darwinian Revolution", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):33.

Ruse, Michael (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution, as seen in 1979 and as seen Twenty-Five Years Later in 2004", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):3.

Hodge, Jonathan (2005), "Against "Revolution" and "Evolution"", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):101.

Herbert, Sandra (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution Revisited", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):51.

Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005), "The Darwinian Revolution as Viewed by a Philosophical Biologist", Journal of the History of Biology 38 (1):123.

Mayr, Ernst (1982), The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

——— (1996), "What is a species, and what is not?" Philosophy of Science 2:262–277.

——— (1997), This is biology: the science of the living world. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Not cooking frogs

Talking Points Memo links to a number of debunkings of the myth that a frog will stay in a gradually heated pot and so boil. Yet Another Thing Everybody Knows that is false. J.B.S. Haldane called this the Aunt Jobisca Theorem: it is a thing that everyone knows.

Possible cause of the Permian extinction

Researchers have found a 300 mile (that's around 480km in real money) crater beneath the Antarctic ice sheet that dates to around the time of the Permian extinction. Bolides seem to be at or near most of the major extinctions. I wonder, idly*, if the impacts themselves aren't the killer blow but rather the subsequent tectonic vulcanism.

* Idly = "wild eyed guess with no evidence or real understanding. Just for future reference, OK?

* Idly = "wild eyed guess with no evidence or real understanding. Just for future reference, OK?

Invade America, and establish democracy there!

A while back I was at a dinner sitting next to Pete Richerson, a lovely guy who is an ornithologist who has written with Robert Boyd (who I haven't met, but I'm sure he's just as nice) some of the most sophisticated and sensible material on cultural evolution - it figures anyone who has to deal with the hyperintelligent Corvidae and other passerine birds would be interested in that. But the talk turned, being mid 2005, to what was going on in Iraq, which had been invaded to bring democracy to Iraqis (or were we still dealing with weapons of mass imagination then? I forget).

In the course of it I happened to elicit a sharp laugh from Pete when I suggested that we should invade the United States - it sorely needed democracy (not having much of it at present) and it certainly had weapons of mass destruction. I was joking, of course. Right?

But today, Leiter Reports link to an article in Rolling Stone that indicates that not only the 2000, but also the 2004 presidential election, was systematically stolen by deliberate fraud and vote rigging. Gore should have won, and Kerry should have won, but the GOP appartchiks made it harder for Democrats to vote, by closing booths, sending voter registration forms too late, or miscounting. Read the article. It's frightening.

Gaining power by vote fraud is a mark of totalitarian regimes subverting democracy. It happened in Russia, in Germany, in Spain and a host of other places. Here's my dilemma - I like America enormously. My visits there have been marked by the richness of the culture, the diversity of places, and the hospitality of the people. I even got to like their accents a bit. But I hate the way its polity is developing and fear not only what will happen when the 200lb gorilla starts throwing its weight around to force its quandam allies to conform to its narrow minded policies (as it has with the previous war on abstract notions, the expensive War on Drugs), but also when likeminded totalitarians in my and other countries start to gain support and comfort from the rise of the totality in the US.

To prevent this, the entire rest of the world needs to invade the US and establish democracy. I'm joking, right?

In the course of it I happened to elicit a sharp laugh from Pete when I suggested that we should invade the United States - it sorely needed democracy (not having much of it at present) and it certainly had weapons of mass destruction. I was joking, of course. Right?

But today, Leiter Reports link to an article in Rolling Stone that indicates that not only the 2000, but also the 2004 presidential election, was systematically stolen by deliberate fraud and vote rigging. Gore should have won, and Kerry should have won, but the GOP appartchiks made it harder for Democrats to vote, by closing booths, sending voter registration forms too late, or miscounting. Read the article. It's frightening.

Gaining power by vote fraud is a mark of totalitarian regimes subverting democracy. It happened in Russia, in Germany, in Spain and a host of other places. Here's my dilemma - I like America enormously. My visits there have been marked by the richness of the culture, the diversity of places, and the hospitality of the people. I even got to like their accents a bit. But I hate the way its polity is developing and fear not only what will happen when the 200lb gorilla starts throwing its weight around to force its quandam allies to conform to its narrow minded policies (as it has with the previous war on abstract notions, the expensive War on Drugs), but also when likeminded totalitarians in my and other countries start to gain support and comfort from the rise of the totality in the US.

To prevent this, the entire rest of the world needs to invade the US and establish democracy. I'm joking, right?

Thursday, June 01, 2006

Cooking up a species

Here's one I was going to leave until I could read the actual paper, because I am both suspicious and skeptical on the one hand and sympathetic to the underlying rationale on the other. And on the gripping hand...

The sympathy I have is that there truly must be an energy budget involved in speciation. Life is, after all, applied thermodynamics, but there is something (please excuse me!) fishy about this. The thermodynamic budget of a species will depend entirely upon context - its trophic level (position in the food web), the complexity of the ecosystem, its distribution and abundance. You can't tell me that a population of 10,000 fishes speciating over time is energetically equivalent to 100 million fishes of the same overall body size speciating. The energetic cost to speciation depends crucially on a number of individual and contingent parameters.

But, as I say, I'll have to wait to see the paper. Last time I looked it wasn't there, either in this week's edition or early edition.

Writing this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists say higher temperatures near the equator speed up the metabolisms of the inhabitants, fueling genetic changes that actually lead to the creation of new species.There are many errors in this release, not the least being the definition and explanation of a new species, but one ought not attack scientists for the inability of a journalist (or in this case, PR maven) to express themselves properly.

The finding — by researchers from the University of Florida, the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, Harvard University and the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque — helps explain why more living species seem to exist near the equator, a scientific observation made even before naturalist Charles Darwin set sail to South America on the H.M.S. Beagle nearly two centuries ago.

It may also have a bearing on concepts such as global warming and efforts to preserve diversity of life on Earth.

“We’ve shown that there is indeed a higher rate of evolutionary change in the form and structure of plankton in the tropics and that it increases exponentially because of temperature,” said James Gillooly, an assistant professor of zoology with the UF Genetics Institute. “It tells us something about the fundamental mechanisms that shape biodiversity on the planet.”

Speciation — when animals or plants actually evolve into a new species — occurs when life forms with a common ancestor undergo substantial genetic change.

Using a mathematical model based on the body size and temperature-dependence of individual metabolism, the researchers made specific predictions on rates of speciation at the global scale. Then, using fossils and genetic data, they looked at rates of DNA evolution and speciation during a 30-million-year period in foraminifera plankton, a single-celled animal that floats in the ocean. Researchers compared arrivals of new species of this type of plankton with differences in ocean temperatures at different latitudes ranging from the tropics to the arctic. The results agreed closely with predictions of their model.

The sympathy I have is that there truly must be an energy budget involved in speciation. Life is, after all, applied thermodynamics, but there is something (please excuse me!) fishy about this. The thermodynamic budget of a species will depend entirely upon context - its trophic level (position in the food web), the complexity of the ecosystem, its distribution and abundance. You can't tell me that a population of 10,000 fishes speciating over time is energetically equivalent to 100 million fishes of the same overall body size speciating. The energetic cost to speciation depends crucially on a number of individual and contingent parameters.

But, as I say, I'll have to wait to see the paper. Last time I looked it wasn't there, either in this week's edition or early edition.

The good that men do

is oft interred with their bones. The evil lives on after them in their posts and papers...

The Explanatory Filter is being revived for SETI. See the post by Pim van Meurs at Panda's Thumb linked above.

The Explanatory Filter is being revived for SETI. See the post by Pim van Meurs at Panda's Thumb linked above.

Microbial species 5: A new beginning

Well after reading many papers by various bacteriologists, mycologists, and other non-vertebrates specialists, I have come to the conclusion that there is no single set of conceptions or criteria (that much abused word!) for something being a species in non-sexual organisms, which I am here calling "microbial". Of course, as I noted, microbes can be "sexual" in various ways. They can share genes via cross-species viral infection (transfection or transduction), via gene fragment uptake (transformation), via sharing in a protosexual way (conjugation), and so on, with it being occasional and rare through to being frequent. They can do this across many clades or only a few. As Butch Cassidy's opponent Harvey Logan observed, there are no rules in a knife fight...

So the Problem of Homogeneity stands in need of explanation. One way it can be explained is in terms of a Branching Random Walk (BRW) with extinction (Pie and Weitz 2005). This generates heterogeneity in the absence of selection even if the extinction is stochastic. If developmental entrenchment is permitted (that is, the longer a gene has been in the lineage, the more tightly developmentally integrated the lineage is to that gene, making change likely to disrupt viability of the organisms, the less heterogeneous the genome distribution, but arguably that involves prior selection for genetic harmony. Still, the "null model" here allows for some heterogeneity just from random events.

As selective pressures are introduced, we get a range of homogeneity-causing processes. Endogenous selection for harmonious genes, which occurs in sexual species through reproductive compatibility, also occurs in microbial species through developmental entrenchment, and possibly also via lateral transfer, although this while sometimes sufficient, appears not to be necessary nor always sufficient. As the frequency and degree of genetic exchange increases, so too does the contribution of exchange to maintaining homogeneity, and this I call endogenous selection.

Ecological selection, or tracking fitness peaks, is, I think, going to be a much stronger "force" in maintaining genomic homogeneity, and this I call exogenous selection. However, given that stochastic "forces" can cause both differentiation (heterogeneity) and clustering (homogeneity), we might expect that ecological selection is indistinguishable from the BRW model, unless there is both a strong signal of ecological adaptation and functionality of the shared genes, and a relative stability of the genome itself. Of course, sometimes neither information is available, but that is an epistemological problem rather than an ontological or causal one.

Note that this is not going to specify exact and constant criteria for microbial specieshood. There are sexual species that are ephemeral, and there are microbial species that have all the "right" preconditions for being a species in place and yet do not behave like them. This is a first-approximation conception of microbial species, and deviants are highlighted by its adoption, so that the reasons why each one is not a species, or species that fail to meet these conditions are, can be further investigated.

That the basic notion of species is a quasipsecies model is not exactly to return to a phenetic or "typological" notion of species*. Rather it is the recognition that there has to be some phenomenally salient clustering of properties for something to be a species. What we do with it afterwards, how we explain it, or identify it, is a matter of empirical work.

Now to sum up the lessons. I argued that the best way to think of microbial, and by extension all sexual, species is twofold: Templeton's Cohesion concept, and Mallet's Genetic Cluster concept. We need to add to this something like de Querioz's General Lineage concept as well. Templeton gives us a causal requirement. Mallet' gives us a phenomenal requirement. De Querioz gives us the evolutionary, or phylogenetic, precondition. We might therefore specify that a species, microbial or otherwise, is this:

* I object to the caricature of types that one finds in the biological literature. Types were always more-or-less notions, and they were rarely, if ever, identified with static entities. It's time to put that notion to bed (Winsor 2003)

References

de Queiroz, Kevin (1998), "The general lineage concept of species, species criteria, and the process of speciation", in Daniel J Howard and Stewart H Berlocher (eds.), Endless forms: species and speciation, New York: Oxford University Press, 57-75.

Mallet, J (1995), "The species definition for the modern synthesis", Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10 (7):294-299.

Pie, Marcio R., and Joshua S. Weitz (2005), "A Null Model of Morphospace Occupation", Am Nat 166 (1):E1-E13. [This paper is not specifically about species concepts, but it transfers nicely to phylogenetic clustering of asexuals.]

Templeton, Alan R. (1989), "The meaning of species and speciation: A genetic perspective", in D Otte and JA Endler (eds.), Speciation and its consequences, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 3-27.

Winsor, Mary Pickard (2003), "Non-essentialist methods in pre-Darwinian taxonomy", Biology & Philosophy 18:387-400.

So the Problem of Homogeneity stands in need of explanation. One way it can be explained is in terms of a Branching Random Walk (BRW) with extinction (Pie and Weitz 2005). This generates heterogeneity in the absence of selection even if the extinction is stochastic. If developmental entrenchment is permitted (that is, the longer a gene has been in the lineage, the more tightly developmentally integrated the lineage is to that gene, making change likely to disrupt viability of the organisms, the less heterogeneous the genome distribution, but arguably that involves prior selection for genetic harmony. Still, the "null model" here allows for some heterogeneity just from random events.

As selective pressures are introduced, we get a range of homogeneity-causing processes. Endogenous selection for harmonious genes, which occurs in sexual species through reproductive compatibility, also occurs in microbial species through developmental entrenchment, and possibly also via lateral transfer, although this while sometimes sufficient, appears not to be necessary nor always sufficient. As the frequency and degree of genetic exchange increases, so too does the contribution of exchange to maintaining homogeneity, and this I call endogenous selection.

Ecological selection, or tracking fitness peaks, is, I think, going to be a much stronger "force" in maintaining genomic homogeneity, and this I call exogenous selection. However, given that stochastic "forces" can cause both differentiation (heterogeneity) and clustering (homogeneity), we might expect that ecological selection is indistinguishable from the BRW model, unless there is both a strong signal of ecological adaptation and functionality of the shared genes, and a relative stability of the genome itself. Of course, sometimes neither information is available, but that is an epistemological problem rather than an ontological or causal one.

Note that this is not going to specify exact and constant criteria for microbial specieshood. There are sexual species that are ephemeral, and there are microbial species that have all the "right" preconditions for being a species in place and yet do not behave like them. This is a first-approximation conception of microbial species, and deviants are highlighted by its adoption, so that the reasons why each one is not a species, or species that fail to meet these conditions are, can be further investigated.

That the basic notion of species is a quasipsecies model is not exactly to return to a phenetic or "typological" notion of species*. Rather it is the recognition that there has to be some phenomenally salient clustering of properties for something to be a species. What we do with it afterwards, how we explain it, or identify it, is a matter of empirical work.

Now to sum up the lessons. I argued that the best way to think of microbial, and by extension all sexual, species is twofold: Templeton's Cohesion concept, and Mallet's Genetic Cluster concept. We need to add to this something like de Querioz's General Lineage concept as well. Templeton gives us a causal requirement. Mallet' gives us a phenomenal requirement. De Querioz gives us the evolutionary, or phylogenetic, precondition. We might therefore specify that a species, microbial or otherwise, is this:

A species is a lineage or set of closely related lineages [De Querioz] that clusters genomically [Mallet] through either stochastic [Pie and Weitz] or cohesive [Templeton] mechanisms and processes, which can be due to exogenous selection tracking fitness peaks or endogenous selection for compatibility with genetic exchange, or some admixture of both.Add to this my Synapomorphic Species Concept, which is a general specification of the notion of biological species rather than a particular conception:

A species is a lineage separated from other lineages by causal differences inand you have more than enough from me on species definitions for now...

synapomorphies.

* I object to the caricature of types that one finds in the biological literature. Types were always more-or-less notions, and they were rarely, if ever, identified with static entities. It's time to put that notion to bed (Winsor 2003)

References

de Queiroz, Kevin (1998), "The general lineage concept of species, species criteria, and the process of speciation", in Daniel J Howard and Stewart H Berlocher (eds.), Endless forms: species and speciation, New York: Oxford University Press, 57-75.

Mallet, J (1995), "The species definition for the modern synthesis", Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10 (7):294-299.

Pie, Marcio R., and Joshua S. Weitz (2005), "A Null Model of Morphospace Occupation", Am Nat 166 (1):E1-E13. [This paper is not specifically about species concepts, but it transfers nicely to phylogenetic clustering of asexuals.]

Templeton, Alan R. (1989), "The meaning of species and speciation: A genetic perspective", in D Otte and JA Endler (eds.), Speciation and its consequences, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 3-27.

Winsor, Mary Pickard (2003), "Non-essentialist methods in pre-Darwinian taxonomy", Biology & Philosophy 18:387-400.

Quote: Ghiselin on the Synthesis

The notion that "the" Synthesis was somehow complete at one time or another in its history implies that the participants were aiming at some culminating event, like the Resurrection of Christ.The canonical texts are being treated as if they were The Gospel according to Saint Doby, The Gospel according to Saint Ernst, The Gospel according to Saint G. G., The Gospel according to Saint Julian, The Gospel according to Saint Bernhard, and The Gospel according to Saint Ledyard. Scientists are explorers, not prophets. For them to display themselves otherwise is as dishonest as it is misleading.

Ghiselin, Michael T. (2001), "Evolutionary synthesis from a cosmopolitan point of view: a commentary on the views of Reif, Junker and Hossfeld", Theory in Biosciences 120:166-172.Can I get an amen!? Amen, brother.

Hobbits and tools

In a hole in the ground there was found a hobbit...

The Independent is reporting objections to the recent claims by the Microcephaly Proponents that the hobbits (Homo floresiensis) had brains that were too small to make the stone tools found with them.

The objections of those proposing that the hobbits were microcephalics strike me as being special pleading in the truest sense - we humans are so special, nothing else could have made these tools. But the ANU team seem to have shown that tools were made by the prior hominid erectus along the same style and method, and that the hobbits probably retained that technology when isolated. It takes big brains perhaps to invent the technology, but it takes only the normal mimetic repertoire of hominid brains to learn how to do this. I'm not even convinced it takes much brain power to invent Acheulian or Olduwan style tools anyway. In fact, given the right circumstances I would think chimps could do it.

Argument by imagination (I can/can't imagine it, therefore it does/doesn't happen that way) is completely bankrupt, in science or out of it. There are more things in heaven and earth than are dream't of in your philosophy, Horatio...

The Independent is reporting objections to the recent claims by the Microcephaly Proponents that the hobbits (Homo floresiensis) had brains that were too small to make the stone tools found with them.

James Phillips, professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said that it was wrong to suggest that the stone tools could have been made by earlier species of humans, such as Homo erectus, a creature that evolved more than 1.8 million years ago and predated modern humans by many hundreds of thousands of years.Good to see this line being taken. If the evidence suggests they did make stone tools, then intuitive preconceptions about brain size and tool making have to go by the wayside. As Grissom says, the evidence does not lie.

"These tools are so advanced that there is no way they were made by anyone other than Homo sapiens," Professor Phillips said.

Now, however, another team of stone-tool experts has cast doubt on this judgement, saying that similar stone tools have been uncovered on the island that clearly predate the arrival of modern Homo sapiens.

Adam Brumm of the Australian National University in Canberra and his colleagues report in the journal Nature that they have found hundreds of almost identical stone tools at a site called Mata Menge just 30 miles away from the Liang Bua cave. They say the tools are between 700,000 and 840,000 years old - too old to have been made by Homo sapiens - and that the production techniques are practically identical to that used at Liang Bua 18,000 years ago.

The objections of those proposing that the hobbits were microcephalics strike me as being special pleading in the truest sense - we humans are so special, nothing else could have made these tools. But the ANU team seem to have shown that tools were made by the prior hominid erectus along the same style and method, and that the hobbits probably retained that technology when isolated. It takes big brains perhaps to invent the technology, but it takes only the normal mimetic repertoire of hominid brains to learn how to do this. I'm not even convinced it takes much brain power to invent Acheulian or Olduwan style tools anyway. In fact, given the right circumstances I would think chimps could do it.

Argument by imagination (I can/can't imagine it, therefore it does/doesn't happen that way) is completely bankrupt, in science or out of it. There are more things in heaven and earth than are dream't of in your philosophy, Horatio...

New cave species found in Israel

Israeli researchers have described eight new species of crustaceans and invertebrates in a recently discovered limestone cave isolated from the external world. They live in and around an underground lake fed by deep water sources rather than rainfall from above.

Israeli researchers have described eight new species of crustaceans and invertebrates in a recently discovered limestone cave isolated from the external world. They live in and around an underground lake fed by deep water sources rather than rainfall from above.

Creationist UK school expels anyone who doesn't conform

The Guardian reports that parents of students at Sir Peter Vardy's Trinity school, the school that gained some notoriety for being partially government funded but also teaching creationism, are complaining that it is expelling students for any kind of religious or cultural nonconformity, thereby selecting both academically and religiously. The school denies this.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

A quote

Francis Bacon wrote of those

that have pretended to find the truth of all natural philosophy in the Scriptures; scandalizing and traducing all other philosophy as heathenish and profane. But there is no such enmity between God's word and His works; neither do they give honour to the Scriptures, as they suppose, but much imbase them. For to seek heaven and earth in the word of God, (whereof it is said, Heaven and earth shall pass, but my word shall not pass,) is to seek temporary things amongst eternal: and as to seek divinity in philosophy is to seek the living amongst the dead, so to seek philosophy in divinity is to seek the dead amongst the living: neither are the pots or lavers, whose place was in the outward part of the temple, to be sought in the holiest place of all, where the ark of the testimony was seated. And again, the scope or purpose of the spirit of God is not to express matters of nature in the Scriptures, otherwise than in passage, and for application to man's capacity, and to matters moral or divine.

Advancement of Learning, Bk II.XXV.16, p216-7 in the Everyman edition.

I'll get back to microbial species, I promise...Monday, May 29, 2006

Microbial species 4a: monophyly and species

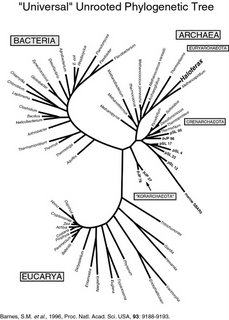

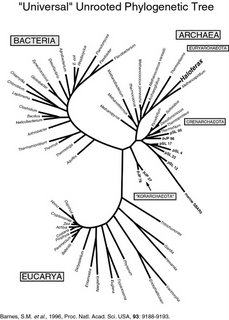

Here is a nice image that shows that even among eukaryotes, reciprocal monophyly is not always the case for species. It's from a paper in PLOS Computational Biology critical of the DNA Barcoding proposal.

Each version shows two species, X and Y. In A, X and Y are reciprocally monophyletic, which means that the coalescent (or last common shared genomic node in the tree, shown by the open stars) is different for each of them and is not nested within either. In B, Y is nested in X, and so X is paraphyletic, although Y is monophyletic. In C, X and Y are interspersed, phylogenetically, in each other, and so each species is polyphyletic and share a coalescent.

Of course in sexual species this raises the question of what makes X and Y species in the latter two cases (that is, why do we think they are different species? The usual answer is either based on mating behaviours, ecology or morphology, or some mix of these) but in asexuals this will occur when the two species cluster genomically as quasispecies in different ways despite being convergently evolved.

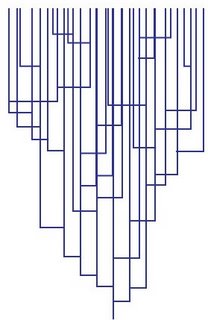

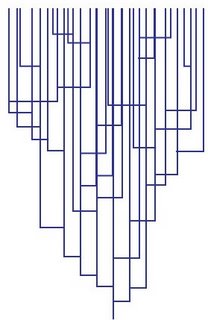

Evolving Thoughts up a tree

Well, everybody's doing it (doing it, doing it) so I have to. Yes, if everybody else jumped off a cliff I would too, mum. This is what the HTML tags look like for this site when run through the websitesasgraphs Java Applet. It is also what the mental contents of my my brain look like when viewed through any medium at all.

Well, everybody's doing it (doing it, doing it) so I have to. Yes, if everybody else jumped off a cliff I would too, mum. This is what the HTML tags look like for this site when run through the websitesasgraphs Java Applet. It is also what the mental contents of my my brain look like when viewed through any medium at all.I can't believe Pharyngula's was so tidy. Maybe his HTML is cleaner than mine, or maybe he cheated by not including the 6000 year archive from his old site; his brain is certainly no tidier than mine, I warrant...

State religion encroaching on military freedoms to believe

While I'm working through the conceptual tangle I've gotten myself in over microbial species. allow me to mention this item from Mike Dunford's The Questionable Authority: apparently the US Army National Cemetery Administration will not permit Wiccans to use a symbol for the headstones of dead veterans.

Guys, the reason why there's a separation of church and state in the first place is because of just this sort of encroachment. If you aren't of an "approved" religion (and note that despite the present President's prior comments about Wiccans in the military, Wicca is an approved religion in the US military anyway), you get sidelined. Doesn't matter that you gave your life for your nation (or for the policies of the same Administration at least). You can't be remembered as the person that you were.

Religion in public affairs has an inbuilt disposition to encroach upon the freedoms of others, whether they are religious or not. It seems to me this is conveniently overlooked by those of the majority religions when it suits them, and they scream loudly when it harms their own interests, perceived or otherwise, or goals and aims. But one never sees atheism or agnosticism encroaching on religion in a secular society (I think that the Soviet and Maoist communisms were not secular, but a form of state religion). This must be why all those majority Christians claim there is a war on religion, when agmostics, atheists and members of minority religions don't like being subsumed under the ruling majority.

How does a religion even get approval? Is there a Senate standing committee that reviews applications for state approval of religion? I thought that was the sort of thing that the Cold War was notionally about...

Good thing I'm not in the US military (well, actually, there are many reasons why that is a good thing, not least for those who might have had to rely on me in combat). If I died in service I'd want to be buried under a very large question mark. That would be appropriate for an agnostic. Although if I died in combat, I'd probably also want a large exclamation mark too. Not for nothing do compositors call it a "shriek", "screamer", or "bang".

Late note: see this post from Dispatches from the Culture Wars for more background.

Guys, the reason why there's a separation of church and state in the first place is because of just this sort of encroachment. If you aren't of an "approved" religion (and note that despite the present President's prior comments about Wiccans in the military, Wicca is an approved religion in the US military anyway), you get sidelined. Doesn't matter that you gave your life for your nation (or for the policies of the same Administration at least). You can't be remembered as the person that you were.

Religion in public affairs has an inbuilt disposition to encroach upon the freedoms of others, whether they are religious or not. It seems to me this is conveniently overlooked by those of the majority religions when it suits them, and they scream loudly when it harms their own interests, perceived or otherwise, or goals and aims. But one never sees atheism or agnosticism encroaching on religion in a secular society (I think that the Soviet and Maoist communisms were not secular, but a form of state religion). This must be why all those majority Christians claim there is a war on religion, when agmostics, atheists and members of minority religions don't like being subsumed under the ruling majority.

How does a religion even get approval? Is there a Senate standing committee that reviews applications for state approval of religion? I thought that was the sort of thing that the Cold War was notionally about...

Good thing I'm not in the US military (well, actually, there are many reasons why that is a good thing, not least for those who might have had to rely on me in combat). If I died in service I'd want to be buried under a very large question mark. That would be appropriate for an agnostic. Although if I died in combat, I'd probably also want a large exclamation mark too. Not for nothing do compositors call it a "shriek", "screamer", or "bang".

Late note: see this post from Dispatches from the Culture Wars for more background.

Saturday, May 27, 2006

How not to apply evolution to culture

Here is a small piece in the Korea Herald, by Arne Jernelov on how evolution explains cultural excellence. It's all about sexual selection, you see - if you do something that is very hard and very costly, you are attracting mates, and this explains sports, painting, literature and science. It is only coincidental that the author is a scientist (an environmental biochemist). I bet he also plays sport competitively.

Friday, May 26, 2006

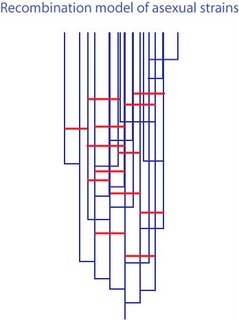

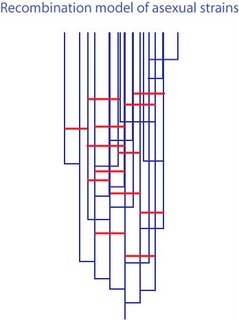

Microbial species 4: degrees of sex

When we attempt to apply to organisms that are not obligately sexual (that is, which don't have to have sex to reproduce) concepts that were specified to use with those that are, we have problems. The Recombination Model is one such attempt. Sure, some microbial species exchange genes. Others do it more frequently and more completely. There appears to be a continuum of gene exchange all the way from almost never to almost every time. So why should we expect that gene transfer will provide us with the sort of homogeneity of lineages and quasispecies that it does in obligate sexuals?

In part I believe this is because we always start from what we know. As I mentioned, the existence and ubiquity of asexual organisms has been resisted from a long time, and treated as exceptional rather than the rule, because biology began with large scale plants and animals, where the paradigm cases were encountered for the biospecies concept. As exceptional cases were encountered, these concepts were stretched, and modified, to serve the increasingly "deviant" cases, until now we realise that deviance is relative to the paradigm conceptions rather than a fact about the organisms. What should we say instead?

I believe we should treat this continuum idea more seriously and as the basis from which the metazoan and metaphyte conceptions are drawn out. And we should consider how the two factors of the Templeton conception - exchange and ecological niche - play differing roles according to the degree of sex a lineage has.

Before I deal with this in detail, let me note for the record that there can be, and must certainly often be, other reasons why the carpet is not smooth, but is patchy. Extinction can cause there to be patches in genome space. Some varieties die out. While this can be because of selection, often it will be due to plain old genetic drift, and contingency. A lineage of asexuals can stochastically drift due to random biases in the direction of mutation, for instance, while earlier forms can go extinct simply because of random drift or random termination of that clone. Moreover, if a genome evolves in a habitat that is sensitive to sudden changes in climate or even geological change that degrades it, then that genome and its neighbours will become extinct. Evolution doesn't explore the same coordinates in genome space all the time and everywhere. This is similar to the phylogenetic trends that occur through simple stochasticity, because clonal evolution is phylogeny.

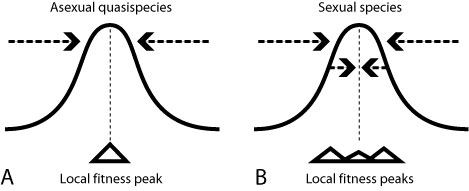

So, back to the notion that sex is not an all-or-nothing affair, so to speak. If the continuum ranges from 0% gene exchange (total asexuality) to 50% gene exchange (total sexuality), then it follows that at the asexual end, exchange can have only limited to no effect on maintaining homogeneity, while at the sexual end, it can have a very great role in maintaining homogeneity. Likewise, at the asexual end, homogeneity not due to stochastic effects will be due largely to ecological selection (fitness peak tracking), while for sexuals this will not be so great a cause. I have given a schematic graph to illustrate this.

This will be why we find that gene exchange doesn't have a simple relationship to genomic homogeneity. It will depend on the rate and amount of genes shared across lineages case by case, as well as the degree to which the quasispecies is maintained by ecological interchangeability. Following on from my discussion about speciation earlier, and my 2001 paper on species concepts, where I employed this evolutionary aspect of the nature of sex to argue that being a species is an evolved trait, not a natural kind, we ought to expect that each species and group of species has its own unique evolutionary history and therefore properties, just as limbs and lungs and livers do. There will be a more general theoretical context of adaptive landscapes, genetic dynamics, and so on, but given that each evolutionary group has encountered different conditions, this means that each modality will be shared in a fairly limited way.

Moreover, this means that biospecies is not the most basal notion of species. In fact, biospecies, or reproductive conceptions of species in general, are derived modalities. The basal notion is quasispecies. All species are at least quasispecies; some are in addition reproductive cohesion or isolation conceptions. This means that some standard requirements for biospecies, such as reciprocal monophyly, do not need to apply to all species. But there is one rather interesting aspect to this approach that I find illuminating, although your mileage may vary: a simple quasispecies is cohered by more or less one adaptive peak (if it is cohered; stochastic clustering does not imply this), while a biospecies famously can be and often is adapted as a generalist or have polytypic traits for differing adaptive peaks.

What maintains a sexual species in this case will be, therefore, the combination of extrinsic selection, and internal or intrinsic cohesion, due to selection for reproductive compatibility with potential mates. I have a paper forthcoming in Biology and Philosophy which argues this in detail. Microbial species will tend to depend on adaptive peak cohesion inversely to the degree that they do share their genes and directly to what functional value of those genes they share have ecologically.

Enough for now. I'll wrap up this series next post.

In part I believe this is because we always start from what we know. As I mentioned, the existence and ubiquity of asexual organisms has been resisted from a long time, and treated as exceptional rather than the rule, because biology began with large scale plants and animals, where the paradigm cases were encountered for the biospecies concept. As exceptional cases were encountered, these concepts were stretched, and modified, to serve the increasingly "deviant" cases, until now we realise that deviance is relative to the paradigm conceptions rather than a fact about the organisms. What should we say instead?

I believe we should treat this continuum idea more seriously and as the basis from which the metazoan and metaphyte conceptions are drawn out. And we should consider how the two factors of the Templeton conception - exchange and ecological niche - play differing roles according to the degree of sex a lineage has.

Before I deal with this in detail, let me note for the record that there can be, and must certainly often be, other reasons why the carpet is not smooth, but is patchy. Extinction can cause there to be patches in genome space. Some varieties die out. While this can be because of selection, often it will be due to plain old genetic drift, and contingency. A lineage of asexuals can stochastically drift due to random biases in the direction of mutation, for instance, while earlier forms can go extinct simply because of random drift or random termination of that clone. Moreover, if a genome evolves in a habitat that is sensitive to sudden changes in climate or even geological change that degrades it, then that genome and its neighbours will become extinct. Evolution doesn't explore the same coordinates in genome space all the time and everywhere. This is similar to the phylogenetic trends that occur through simple stochasticity, because clonal evolution is phylogeny.

So, back to the notion that sex is not an all-or-nothing affair, so to speak. If the continuum ranges from 0% gene exchange (total asexuality) to 50% gene exchange (total sexuality), then it follows that at the asexual end, exchange can have only limited to no effect on maintaining homogeneity, while at the sexual end, it can have a very great role in maintaining homogeneity. Likewise, at the asexual end, homogeneity not due to stochastic effects will be due largely to ecological selection (fitness peak tracking), while for sexuals this will not be so great a cause. I have given a schematic graph to illustrate this.

This will be why we find that gene exchange doesn't have a simple relationship to genomic homogeneity. It will depend on the rate and amount of genes shared across lineages case by case, as well as the degree to which the quasispecies is maintained by ecological interchangeability. Following on from my discussion about speciation earlier, and my 2001 paper on species concepts, where I employed this evolutionary aspect of the nature of sex to argue that being a species is an evolved trait, not a natural kind, we ought to expect that each species and group of species has its own unique evolutionary history and therefore properties, just as limbs and lungs and livers do. There will be a more general theoretical context of adaptive landscapes, genetic dynamics, and so on, but given that each evolutionary group has encountered different conditions, this means that each modality will be shared in a fairly limited way.

Moreover, this means that biospecies is not the most basal notion of species. In fact, biospecies, or reproductive conceptions of species in general, are derived modalities. The basal notion is quasispecies. All species are at least quasispecies; some are in addition reproductive cohesion or isolation conceptions. This means that some standard requirements for biospecies, such as reciprocal monophyly, do not need to apply to all species. But there is one rather interesting aspect to this approach that I find illuminating, although your mileage may vary: a simple quasispecies is cohered by more or less one adaptive peak (if it is cohered; stochastic clustering does not imply this), while a biospecies famously can be and often is adapted as a generalist or have polytypic traits for differing adaptive peaks.

What maintains a sexual species in this case will be, therefore, the combination of extrinsic selection, and internal or intrinsic cohesion, due to selection for reproductive compatibility with potential mates. I have a paper forthcoming in Biology and Philosophy which argues this in detail. Microbial species will tend to depend on adaptive peak cohesion inversely to the degree that they do share their genes and directly to what functional value of those genes they share have ecologically.

Enough for now. I'll wrap up this series next post.

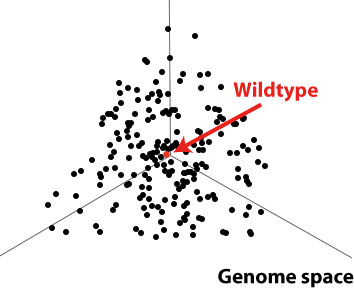

Microbial species 3: Quasispecies and ecology

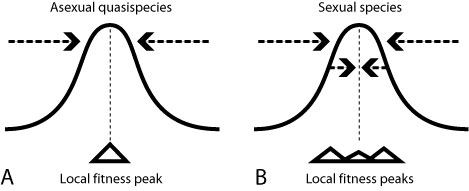

The second main approach to a natural conception of microbial species (by which I mean, as opposed to operational, practical or conventional ones, collectively called "artificial" conceptions) is what I will call the Quasispecies Model. According to the concept developed by Manfred Eigen for viral species, a quasispecies ("as-if-species") is a cluster of genomes in a genome space of the dimensionality the number of loci. A quasipecies is in effect a cloud of genomes, with a "wild-type" coordinate (that is, genome) that may or may not actually have an extant or extinct instance.

A genetic cluster of the quasispecies kind is therefore not unlike James Mallet's Genotypic Cluster Concept (1995), although this is primarily an operational definition than a substantive underlying account of species. We still need to account for quasispecies existing in the first place. We have considered one possible mechanism - gene sharing by lateral transfer - and found it to be insufficient. Is there something else we might make use of?

There is one proposal by Alan Templeton (1989), devised for sexual organisms, which defines a species as a genetic cluster, as Mallet's does, but accounts for it either by genetic exchange, as in the recombination model, or ecological interchangeability. This latter notion is what we might call the "Fitness Peak Conception" of quasispecies.

Each coordinate in genome space, that is to say each genome, has a fitness value associated with it that is imposed by ecological factors. If the adaptive landscape is relatively smooth, which means that adjacent coordinates are correlated in their fitness values, we should expect in the absence of all other causes of clustering that the cloud of genomes will tend to centre upon the most adaptive genome. Of course, this is an abstraction and a gross simplification - genomes are not independent of each other, or from fitness values. Organisms create their ecological conditions to a degree, and how fit a genome is depends also upon what other genomes exist in a population (at least, in sexual organisms), but we can leave these complications to one side for the moment.

So one potential reason why quasispecies exist, why genomes cluster, is that they track local fitness peaks. Let's flesh this out, so to speak. Take a pathogen that is clonal. It needs to employ certain features of the host species in order to infect and exploit that host. Assuming these don't change - say they are recognition molecules on a cell surface - the quasispecies will cluster about those point in the genome space that are more effective than others with respect to the capacity to infect and exploit.

So now we have the two cohesion mechanisms proposed by Templeton - cohesion due to shared genes, and cohesion due to the need to exploit the environment better than competitors. Anything that can do well at the latter will tend to be better represented in the average population. Hence quasispecies.

But fitness peaks typically do not remain constant or decoupled from the populational structure, as I said. Does this mean that quasispecies are not real species because they are ephemeral? Of course not - all species are, over a suitably extended timescale, ephemeral. That is in the nature of evolution. What the fitness peak conception means is that a quasispecies will remain homogeneous so long as there is a more or less unitary fitness peak. If the peaks shift, there will be "speciation". Oh heck, let's stop the pretense that quasispecies aren't real species. There will be real speciation.

In the next blog, I will discuss a way to bring these two notions together, and to link quasispecies with biospecies (sexual species).

Eigen, Manfred (1993), "The origin of genetic information: viruses as models", Gene 135 (1-2):37–47.

——— (1993), "Viral quasispecies", Scientific American July 1993 (32-39).

Mallet, J (1995), "The species definition for the modern synthesis", Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10 (7):294-299.

Templeton, Alan R. (1989), "The meaning of species and speciation: A genetic perspective", in D Otte and JA Endler (eds.), Speciation and its consequences, Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 3-27.

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Microbial species 2: recombination

The cluster of genomes of asexual organisms forms what is called a "phylotype" (Denniston 1974, a term coined by C. W. Cotterman in unpublished notes dated 1960; I like to track these things down). Phylotype is a taxon-neutral term, though, that is determined entirely by the arbitrary level of genetic identity chosen. For example, "species" in asexuals might be specified as being 98%+ similarity of genome, or it might be 99.9%+ (I have seen both in the literature). A phylotype of, say 67% or 80% might be used for other purposes (such as identifying a disease-causing group of microbes).

The phylotype concept, while useful in other respects, reinvents (or preinvents - 1960 predates the work of Sokal and Sneath) phenetics. A phenetic taxon was called the Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) and it used an arbitrary measure of similarity and difference: an 80% "phenon line" was the arbitrary measure for species based on phenotypic similarities. The problem was that the distances changes as you chose different principal components, and I warrant the same is true for phylotypes.

One solution to the Problem of Homogeneity for asexuals is what I will call the Recombination Species Concept. Proposed by Dykhuizen and Green in 1991, it basically the Biological Species Concept for lineages that occasionally share genes or gene fragments through lateral transfer.

There are several mechanisms by which lateral transfer of DNA can occur among "prokaryotes". One is DNA fragment reuptake, in which DNA from a cell that has lysed (its membrane or wall has disintegrated, releasing the cell contents into the medium) is taken up by another cell, and rather than being digested it becomes active. There are variations on this. Entire chromosomal rings, called plasmids can be taken up this way. Or a cell can "bleb", forming vesicles or compartments of lipids, containing DNA (including plasmids), which then attach to the receiving cell, opening up to the interior.

I mentioned prokaryotes before. This refers broadly to a paraphyletic group of organisms that are basically not-eukaryotes. Nowadays we refer instead to several groups: Bacteria, Archaea (which is sometimes decomposed into several other groups), and Eukaryota. One thing the not-Eukaryotes have in common, though, is a lack of a nuclear membrane, allowing the transfer of genetic material between genomes.

I mentioned prokaryotes before. This refers broadly to a paraphyletic group of organisms that are basically not-eukaryotes. Nowadays we refer instead to several groups: Bacteria, Archaea (which is sometimes decomposed into several other groups), and Eukaryota. One thing the not-Eukaryotes have in common, though, is a lack of a nuclear membrane, allowing the transfer of genetic material between genomes.

So the Recombination model of microbial species is based on the claim that the greater the genetic distance between strains, the less likely it is that the genes will be functional and useful in the receiving strain, and this is what serves to maintain the homogeneity of bacterial and other microbial species. One of the claims is in fact that the differences in genetic structure, and in some cases differences in restriction enzymes, that break DNA sequences, will make a nonsense of the DNA fragment or insert it in a nonfunctional location in the target genome.

These compatibility issues act like sex does to maintain the overall "location" in genome space of the population. Those strains that deviate too far from the mode will be unable to take up the functionally useful lateral genes, and so will be more susceptible to extinction through genetic load.

So the Recombination model is a mix of Maynard Smith's theory of sex, and Mayr's notion of biological species. The only problem is that it isn't consistently true. A beautiful explanation is spoiled by ugly facts. Recombination via lateral transfer appears to be rather more profligate than first appeared (Beiko, et al. 2005), and there are some "species" of bacteria, such as the Lyme Disease-causing spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, that appear not to share genes much, if at all (as Dykhuizen himself observes, Dykhuizen and Baranton 2001). So if in those cases clustering occurs, it is not due to lateral transfer, but some other processes.

I failed to mention a process that is directly analogous to sex in bacteria - conjugation. This is a case where part of the genetic component, usually plasmids, which are secondary small chromosomes (B), or the main nucleoid (A), can be inserted into another cell via processes called pili, which are part of the Type IV secretory system used for other purposes and which is homologous to flagella. The typical mode of conjugation is that one mating type (often called the "male") is activated by pheromones from another mating type ("female") to attach the pilus to the recipent, and insert the genetic material.

I failed to mention a process that is directly analogous to sex in bacteria - conjugation. This is a case where part of the genetic component, usually plasmids, which are secondary small chromosomes (B), or the main nucleoid (A), can be inserted into another cell via processes called pili, which are part of the Type IV secretory system used for other purposes and which is homologous to flagella. The typical mode of conjugation is that one mating type (often called the "male") is activated by pheromones from another mating type ("female") to attach the pilus to the recipent, and insert the genetic material.

Now this is "almost-sex", because there is no genetic reassortment, but other processes will tend to shuffle genes into the nucleoid, as well as utilising the taken-up plasmids. But again, while the mating types seem to act as cohesive mechanisms, conjugation can be profilgate across large, even vast, phylogenetic distances (and hence genetic distances). It has been observed between bacteria and yeast, bacteria and plants, and there has even been a case in which it was observed between bacteria (E. coli) and mammalian (hamster) cells (Waters 2001).

So while it may be that recombination of lineages through partial genetic transfer operates as a reason for some phylotypes, it does not account for all, and is therefore not a sine qua non of specieshood, or homogeneity, among microbes.

Next, we'll consider ecological accounts, as well as drift, migration and geographical isolation.

Beiko, Robert G., Timothy J. Harlow, and Mark A. Ragan (2005), "Highways of gene sharing in prokaryotes", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 102 (40):14332-14337.

Denniston, Carter (1974), "An extension of the probability approach to genetic relationships: One locus", Theoretical Population Biology 6 (1):58-75.

Dykhuizen, D. E., and G. Baranton (2001), "The implications of a low rate of horizontal transfer in Borrelia", Trends in Microbiology 9 (7):344-350.

Dykhuizen, D. E., and L. Green (1991), "Recombination in Escherichia coli and the definition of biological species", Journal of Bacteriology 173 (22):7257-7268.

Waters, V. L. (2001), "Conjugation between bacterial and mammalian cells", Nature Genetics 29 (4):375-376.

The phylotype concept, while useful in other respects, reinvents (or preinvents - 1960 predates the work of Sokal and Sneath) phenetics. A phenetic taxon was called the Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) and it used an arbitrary measure of similarity and difference: an 80% "phenon line" was the arbitrary measure for species based on phenotypic similarities. The problem was that the distances changes as you chose different principal components, and I warrant the same is true for phylotypes.

One solution to the Problem of Homogeneity for asexuals is what I will call the Recombination Species Concept. Proposed by Dykhuizen and Green in 1991, it basically the Biological Species Concept for lineages that occasionally share genes or gene fragments through lateral transfer.

There are several mechanisms by which lateral transfer of DNA can occur among "prokaryotes". One is DNA fragment reuptake, in which DNA from a cell that has lysed (its membrane or wall has disintegrated, releasing the cell contents into the medium) is taken up by another cell, and rather than being digested it becomes active. There are variations on this. Entire chromosomal rings, called plasmids can be taken up this way. Or a cell can "bleb", forming vesicles or compartments of lipids, containing DNA (including plasmids), which then attach to the receiving cell, opening up to the interior.

I mentioned prokaryotes before. This refers broadly to a paraphyletic group of organisms that are basically not-eukaryotes. Nowadays we refer instead to several groups: Bacteria, Archaea (which is sometimes decomposed into several other groups), and Eukaryota. One thing the not-Eukaryotes have in common, though, is a lack of a nuclear membrane, allowing the transfer of genetic material between genomes.

I mentioned prokaryotes before. This refers broadly to a paraphyletic group of organisms that are basically not-eukaryotes. Nowadays we refer instead to several groups: Bacteria, Archaea (which is sometimes decomposed into several other groups), and Eukaryota. One thing the not-Eukaryotes have in common, though, is a lack of a nuclear membrane, allowing the transfer of genetic material between genomes.

So the Recombination model of microbial species is based on the claim that the greater the genetic distance between strains, the less likely it is that the genes will be functional and useful in the receiving strain, and this is what serves to maintain the homogeneity of bacterial and other microbial species. One of the claims is in fact that the differences in genetic structure, and in some cases differences in restriction enzymes, that break DNA sequences, will make a nonsense of the DNA fragment or insert it in a nonfunctional location in the target genome.

These compatibility issues act like sex does to maintain the overall "location" in genome space of the population. Those strains that deviate too far from the mode will be unable to take up the functionally useful lateral genes, and so will be more susceptible to extinction through genetic load.

So the Recombination model is a mix of Maynard Smith's theory of sex, and Mayr's notion of biological species. The only problem is that it isn't consistently true. A beautiful explanation is spoiled by ugly facts. Recombination via lateral transfer appears to be rather more profligate than first appeared (Beiko, et al. 2005), and there are some "species" of bacteria, such as the Lyme Disease-causing spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, that appear not to share genes much, if at all (as Dykhuizen himself observes, Dykhuizen and Baranton 2001). So if in those cases clustering occurs, it is not due to lateral transfer, but some other processes.

Now this is "almost-sex", because there is no genetic reassortment, but other processes will tend to shuffle genes into the nucleoid, as well as utilising the taken-up plasmids. But again, while the mating types seem to act as cohesive mechanisms, conjugation can be profilgate across large, even vast, phylogenetic distances (and hence genetic distances). It has been observed between bacteria and yeast, bacteria and plants, and there has even been a case in which it was observed between bacteria (E. coli) and mammalian (hamster) cells (Waters 2001).

So while it may be that recombination of lineages through partial genetic transfer operates as a reason for some phylotypes, it does not account for all, and is therefore not a sine qua non of specieshood, or homogeneity, among microbes.

Next, we'll consider ecological accounts, as well as drift, migration and geographical isolation.

Beiko, Robert G., Timothy J. Harlow, and Mark A. Ragan (2005), "Highways of gene sharing in prokaryotes", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 102 (40):14332-14337.

Denniston, Carter (1974), "An extension of the probability approach to genetic relationships: One locus", Theoretical Population Biology 6 (1):58-75.

Dykhuizen, D. E., and G. Baranton (2001), "The implications of a low rate of horizontal transfer in Borrelia", Trends in Microbiology 9 (7):344-350.

Dykhuizen, D. E., and L. Green (1991), "Recombination in Escherichia coli and the definition of biological species", Journal of Bacteriology 173 (22):7257-7268.

Waters, V. L. (2001), "Conjugation between bacterial and mammalian cells", Nature Genetics 29 (4):375-376.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

On microbial species

OK, this is one of a series of posts in which I will play with ideas that might become a paper.

The problem is this: usually we define a species as a group of related organisms that share genes (or a gene pool, which amounts to the same thing). Sometimes we include also ecological considerations (either in the form of natural selection, or in terms of sharing a niche).

But many microbial species either do not share genes to reproduce, or they can but do not need to. So, the question is sometimes raised whether microbes (of this kind) form species at all, or if there is some replacement term or concept for microbial taxonomy.

Historically, it took a long time to even accept that there were asexual organisms. Darwin discussed hermaphroditic species, but they still had mating types or genders; it was just that a single individual had both kinds. It was long recognised that some plants could propagate vegetatively. But the notion that there were obligately asexual organisms was doubted, for instance, by Fisher as late as 1958 (in the second edition of the Genetical Theory of Natural Selection). George Gaylord Simpson, the famous joint architect of the synthesis and paleontologist, simply denied that asexuals formed species. Call them something else, he said.