Speciation genes

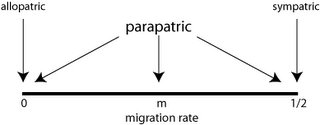

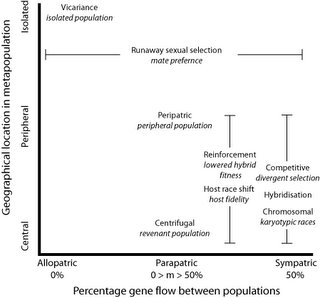

Let's recap. Following Gavrilets' suggestion, we have concluded that geography is a minor component in the conceptual taxonomy of speciation. The major component is gene flow, and geographical classification merely goes to the nature of the selection involved; whether it is intrinsic (sexual selection, lowered hybrid fitness, karyotypical incompatibility) or extrinsic (ecological). If extrinsic, then the genetic structure of the species can change in ways that inadvertently cause reproductive isolation.

I introduced the notion of reproductive reach - the genetic or developmental "distance" within which fitness is lowered insufficiently to prevent introgression between populations. Some researchers, such as Chung-I Wu and, as RPM notes in the comments to the last post, Will Provine, seek to find "speciation genes" which are modified through this inadvertent selection. This is, I believe, a category mistake, and a logical fallacy.

The category mistake is to presume that because a genetic distance causes speciation, it is therefore a gene "for" speciation. But there is no prior specification of genes that cause reproductive isolation. A genetic change may do so, or it may not. Identifying that it has done so is something that can only be done post hoc. And there appears to be no particular genes that cause speciation over large evolutionary distances - there may be an active gene complex in Drosophila which when changed causes reproductive isolation, but it doesn't therefore follow that a homolog of that complex will do the same thing in other flies, or in insects generally, or in all animals, etc. In fact, it doesn't even follow that we will find this is the complex involved in all cases of Drosophila speciation, either.

Whether or not genetic differences cause isolation depends on the entire complex of the organisms involved. The heterogeneity of the RI chart from Littlejohn shows that there are no singular reasons why interfertility is reduced in all organisms. Finding one that does is not therefore inductively generalisable over all members of the clade - this is the logical fallacy. If the complex G causes RI in species-pair S, to assert that it is therefore the active cause in species-pair S' is a fallacy of affirming the consequent. Or it is a reasonable assumption, just to the extent that S' is closely related to S and there are prior reasons for thinking that G is active in both cases (like mutability of G in that clade).

There is an overwhelming tendency amongst biologists to overgeneralise their results, and this is understandable. Science is about making generalities to cover large phenomenal domains. The trick is to generalise just so much as the data and hypothesis allow, and no further, and of course Nature isn't giving away any hints about how far is too far. But we have seen a "vertebrate bias" among zoologists, a "zoological bias" amongst geneticists and evolutionary biologists of yore (many of whom were animal biologists - Mayr was an ornithologist, Dobzhansky an entomologist, Simpson a vertebrate paleontologist. Verne Grant was the botanist, and his contribution was an afterthought). But evolution is about all living things. General conclusions should be founded on general data.

So we should reject the a priori idea that there will be "speciation genes". Speciation involves entire genomes, plus of course the developmental system in which they are expressed, plus the ecological context in which genes are "normal".

Next, I aim to summarise this in a single chart, and suggest some implications for species concepts, in particular the genetic cohesion concept of Alan Templeton. But this may have to wait until the alcohol wears off, and I get back to the office and my references.

Happy Summer solstice, everybody. For those of you in the Northern hemisphere, sorry about your lack of timing.

Late Correction: It was RPM not RBH who made the observation. My mistake.

I introduced the notion of reproductive reach - the genetic or developmental "distance" within which fitness is lowered insufficiently to prevent introgression between populations. Some researchers, such as Chung-I Wu and, as RPM notes in the comments to the last post, Will Provine, seek to find "speciation genes" which are modified through this inadvertent selection. This is, I believe, a category mistake, and a logical fallacy.

The category mistake is to presume that because a genetic distance causes speciation, it is therefore a gene "for" speciation. But there is no prior specification of genes that cause reproductive isolation. A genetic change may do so, or it may not. Identifying that it has done so is something that can only be done post hoc. And there appears to be no particular genes that cause speciation over large evolutionary distances - there may be an active gene complex in Drosophila which when changed causes reproductive isolation, but it doesn't therefore follow that a homolog of that complex will do the same thing in other flies, or in insects generally, or in all animals, etc. In fact, it doesn't even follow that we will find this is the complex involved in all cases of Drosophila speciation, either.

Whether or not genetic differences cause isolation depends on the entire complex of the organisms involved. The heterogeneity of the RI chart from Littlejohn shows that there are no singular reasons why interfertility is reduced in all organisms. Finding one that does is not therefore inductively generalisable over all members of the clade - this is the logical fallacy. If the complex G causes RI in species-pair S, to assert that it is therefore the active cause in species-pair S' is a fallacy of affirming the consequent. Or it is a reasonable assumption, just to the extent that S' is closely related to S and there are prior reasons for thinking that G is active in both cases (like mutability of G in that clade).

There is an overwhelming tendency amongst biologists to overgeneralise their results, and this is understandable. Science is about making generalities to cover large phenomenal domains. The trick is to generalise just so much as the data and hypothesis allow, and no further, and of course Nature isn't giving away any hints about how far is too far. But we have seen a "vertebrate bias" among zoologists, a "zoological bias" amongst geneticists and evolutionary biologists of yore (many of whom were animal biologists - Mayr was an ornithologist, Dobzhansky an entomologist, Simpson a vertebrate paleontologist. Verne Grant was the botanist, and his contribution was an afterthought). But evolution is about all living things. General conclusions should be founded on general data.

So we should reject the a priori idea that there will be "speciation genes". Speciation involves entire genomes, plus of course the developmental system in which they are expressed, plus the ecological context in which genes are "normal".

Next, I aim to summarise this in a single chart, and suggest some implications for species concepts, in particular the genetic cohesion concept of Alan Templeton. But this may have to wait until the alcohol wears off, and I get back to the office and my references.

Happy Summer solstice, everybody. For those of you in the Northern hemisphere, sorry about your lack of timing.

Late Correction: It was RPM not RBH who made the observation. My mistake.