So, as my commenters have noted, I screwed up. Badly. The paper I cited as having 54 races actually had six clusters those populations fit into. I don't mind - I said at the beginning I was ignorant of this, and these posts are my way of learning about the topic and getting a free education ("Yes! He can be taught!").

Before I respond to the very gracious response by Razib (

I say "race", and you say "population structure"), which raises interesting philosophical questions, let me just tell you all my learning strategy. I have always found that it is best to take a stance on a topic, and make those who would educate or convince you do the hard work of getting you to change your mind. This way, issues have an edge, and they matter. The idea that one should hold judgement in abeyance in education strikes me as a way to promote rote learning and dogmatism.

But the philosophical issues here aren't undercut by my misreading science. I think that there are a number of deeper issues, which underpin our thinking on matters of detail. Let me see if I can outline them.

1. Classification

Typically we have classified throughout the western era in terms of resemblances. Racial classification is only one of these. There are two main ways to classify things, especially biological things: one is to take a resemblance criterion and identify those who approach or deviate from it. This is known as the

typological way of classifying. You take a type specimen and identify all those who are near enough to it for inclusion. [Side note: despite loose usage by Mayr and others, typology is not the same as essentialism; most biologists have been typologists including modern biologists. Almost none have been essentialists.]

The other is by descent. Darwin introduced a real novelty into classification - ancestry. Previous biologists used ancestry as a way of isolating groups. In Cuvier's definition, for example, a species was all descendents of an original pair. Darwin conjectured that the distributions of groups within groups is due to shared ancestry

between species. This has led to the phylogenetic manner of classification, sometimes known as "cladistics". But cladistics requires that lineages split. If a lineage recombines with related lineages on a regular basis, then cladistics is no use for classification. Such recombining lineages are called

tokogenetic in cladistic terminology. The reason these are uninformative is that the "signal" of past history is lost. But it doesn't follow that the signal is lost for

genes within that species - we can treat them as self-standing lineages that have recoverable histories even if the groups which comprise them are not clades.

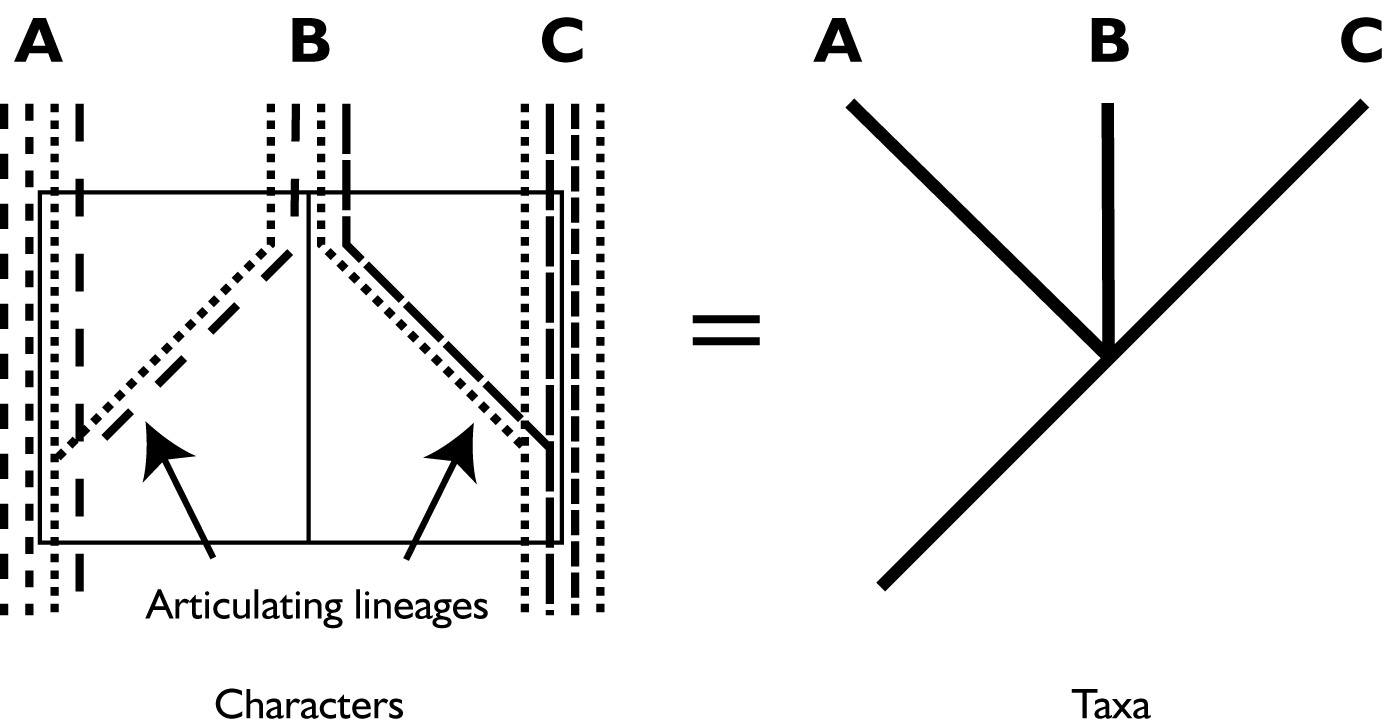

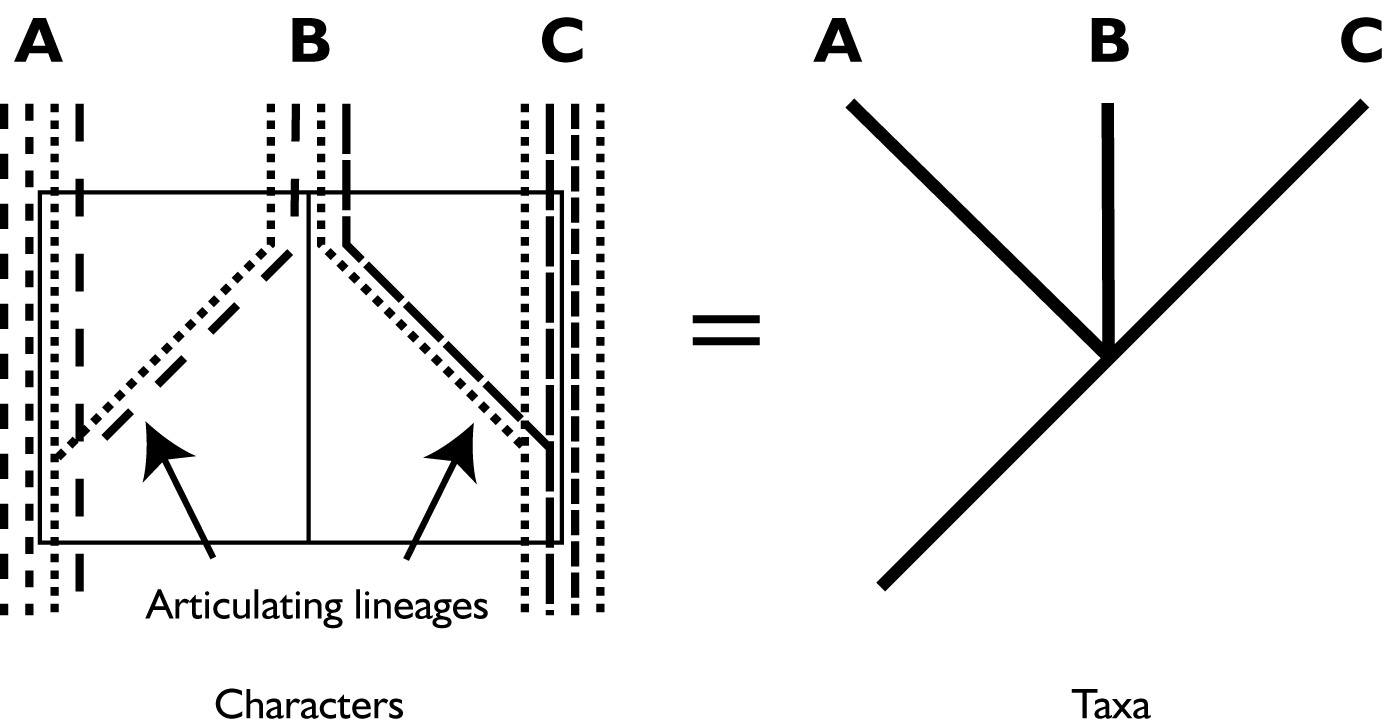

I once used a figure in a

paper to illustrate this:

We can recover the history of the genes (here, the characters) even if we cannot recover the history of populations as such. Genes are at best surrogates for population structure. But they don't, of themselves, make taxa such as races. And using resemblance classes to form racial classification is very sensitive to the identification keys used.

OK, that's the nitpick, although I find this stuff more fascinating than the usual questions raised about race. That's just me.

The second question is

2. The conceptual and social role of "race"Racial classifications are almost always associated with measures of valuation. that is, we talk often about "advanced" or "civilised" races versus "primitive" or "barbaric" races. I know this is not what was meant by Razib or Matt, but the problem is that simply saying that self-identified races match genetic clustering implies a reality, not to the biological variation, which

is real, but to the underlying semantic connotations of the term. And if the "races" used in the clustering really

do match biological distributions, it implies, and is regularly taken to imply by those who use race in political and social debates, that the valuations are worth using too.

This is an argument from consequences, and might be a fallacy. If races are real, then the social consequences don't make a damn bit of difference to the factuality. But suppose they are not real, but appear to be because of the way we have investigated it, that is, the way we set up the questionnaire. As I said before, you can find covariance between any two sets of categorials if you care to. The impact of this is dramatic. The nuances of the scientific papers will get lost in the ways the science is employed. This is not trivial, and we need to be very careful here. The human tendency is universal to identify and discriminate against outgroups. Scientists no less than anyone else need to ensure that they don't give aid and comfort to the bigots. So I merely say, be

absolutely sure before making claims of the reality of [socially constructed] races.

We humans are pretty good pattern matchers. Like a neural network (because we use them), we can take multivariate inputs and cluster them. But this is not reliable all the time. We can be trained on the wrong data set, for instance. What I am claiming here is that the clusterings are informed by "wrong" data sets to begin with. Rather than trying to match between naive categories and sophisticated and real biological data, perhaps it might be better to see what sorts of clusterings occur just on the basis of the data.

Suppose we do this, and someone will argue that this is what the Rosenberg

et al. paper does do, if there are clusters, does this mean all those clusters are equally of the same "depth"? Is, for instance, the Oceanic group of the same rank or significance as the African? How could that be? We have been in Africa for many times the amount of time we were in Asia or Oceania - the amount of unique allelic variation that could evolve

in situ must be less than that in Africa. So equating the two clusters is already to make a mis-step.

There's a problem of commensuration here that also occurs in cladistics. There are no ranks in evolution apart from those we impose for convenience. It's very important then to ensure that the convenience suits

scientific purposes rather than social ones.

3. Medical issues

One of the main reasons that people today will assert the reality of race is based on the genetic components of things like malarial resistance, lactose intolerance, resistance to various diseases like

Yersinia pestis (bubonic plague), and AIDS. There clearly

are geographical variations here. It is sometimes convenient to do a Dr House and say that a given disease is identifiable on racial classification. As a first cut, this might work as an inferential guideline, as a heuristic rule. The problem with such abstractions, or as Razib calls them

abstracta, is that they are only so good as the distributions of properties they cover. What than gnomic utterance means is that if you specify a type, and not all members of the type have the "typical" traits, then you can be

misled as well as informed. Surely it might be better to see what sorts of phenotypic traits covary with the diseases first, before assigning those genes to a phenotypic class.

But Razib has conceded that it doesn't matter from a medical perspective whether we call these races or populations with structure. It does matter than one is likely to suffer from lactose intolerance if one has a substantial east Asian heritage. So let us leave this. I want to play with the

philosophical aspects Razib raises about this:

4. MetaphysicsAh, metaphysics. Meat and drink to a philosopher. Usually not to philosophers of science, though, but I'm atypical (that is, you cannot infer inductively from a knowledge of the type I instantiate to all of my properties <wink>).

Razib says that

we are clashing in the turbulent waters of nominalism

and

the perception by John that I am conceiving of race as an essential and fundamental taxonomical unit. I don't hold to that. I've rejected the Platonic conception of race before.

And so it is. Ultimately this is all about what one thinks classes of things, universals, are. Now while a lot of attack on race concepts focus on "Platonism", I don't, and I don't think Razib is using such a perspective, either. There is a very large difference between saying that something has an essence shared by all its members, to saying that the something is a Platonic form. The former claim is

Aristotelian, not Platonic. The difference is this, and bear with me because it has a payoff in this debate:

Plato's forms are not physical things. They are eternal kinds, that no actual object ever properly instantiates, but at best approximates. Aristotle's forms are always physical things, and the descriptions of those things are what has the essences, not the things themselves. This gets a bit messy, because then we have to talk about "properties", but that will do for now. Nominalism, a later development ironically dealing with the confusion between Platonic and Aristotelian forms by the so-called Neoplatonists, holds that universal properties, of essences, exist solely in the words and in the head. This is exactly the issue about abstraction that I dealt with before.

It is my view that we are born Aristotelian essentialists [see

The Essential Child : Origins of Essentialism in Everyday Thought by Susan A. Gelman] but that we learn in our investigation of the world, that it doesn't rely on the nature of the words we use to describe or explain it.

Now, when we classify our world we are often tempted to reify the groups we class. "Races" are such an item. If there are biological clusters, there are biological clusters, but to call one of these a "race" is to invite belief that there is some shared description that is true of all and only members of that "race", which Razib doesn't believe. So we

should be nominalists about the

abstracta because it hinders our natural tendency to make fallacious inferences from the labels we use.

I better summarise, because otherwise I'll lose more of you than I already have.

- Race refers to well-marked and stable subspecific varieties in a species. Humans do not have these, I believe

- They are abstractions based on our tendencies to recognise variation in a typological manner, informed by our social discriminations

- It is better to generate our abstractions directly from the data to inform our inferential processes, than to claim that prior naive classifications are somehow real. That is, the data explain why we make these discriminations, but they don't license them.

- The social problems of using the naive folk taxonomy of race are so great that we should be careful about using the notion at all.

I think that is all I have worth saying on the matter. Read the comments - they have been very useful in this series of posts.

Late note: RPM at Evolgen has a nice wrap up, although I wonder did I

really start race riots? I hope not.